- Home

- Walter Scott

Rob Roy Page 2

Rob Roy Read online

Page 2

It may, I hope, be some palliative for the resistance which, on this occasion, I offered to my father’s wishes, that I did not fully understand upon what they were founded, or how deeply his happiness was involved in them. Imagining myself certain of a large succession in future, and ample maintenance in the meanwhile, it never occurred to me that it might be necessary, in order to secure these blessings, to submit to labour and limitations unpleasant to my taste and temper. I only saw in my father’s proposal for my engaging in business, a desire that I should add to those heaps of wealth which he had himself acquired; and imagining myself the best judge of the path to my own happiness, I did not conceive that I should increase that happiness by augmenting a fortune which I believed was already sufficient, and more than sufficient, for every use, comfort, and elegant enjoyment.

Accordingly, I am compelled to repeat, that my time at Bourdeaux had not been spent as my father had proposed to himself. What he considered as the chief end of my residence in that city, I had postponed for every other, and would (had I dared) have neglected it altogether. Dubourg, a favoured and benefited correspondent of our mercantile house, was too much of a shrewd politician to make such reports to the head of the firm concerning his only child, as would excite the displeasure of both; and he might also, as you will presently hear, have views of selfish advantage in suffering me to neglect the purposes for which I was placed under his charge. My conduct was regulated by the bounds of decency and good order, and thus far he had no evil report to make, supposing him so disposed; but, perhaps, the crafty Frenchman would have been equally complaisant had I been in the habit of indulging worse feelings than those of indolence and aversion to mercantile business. As it was, while I gave a decent portion of my time to the commercial studies he recommended, he was by no means envious of the hours which I dedicated to other and more classical attainments, nor did he ever find fault with me for dwelling upon Corneille and Boileau, in preference to Postlethwayte, (supposing his folio to have then existed, and Monsieur Dubourg able to have pronounced his name,) or Savary, or any other writer on commercial economy. He had picked up somewhere a convenient expression, with which he rounded off every letter to his correspondent,— ‘I was all,’ he said, ‘that a father could wish.’

My father never quarrelled with a phrase, however frequently repeated, provided it seemed to him distinct and expressive; and Addison himself could not have found expressions so satisfactory to him as, ‘Yours received, and duly honoured the bills enclosed, as per margin.’

Knowing, therefore, very well what he desired me to be, Mr. Osbaldistone made no doubt, from the frequent repetition of Dubourg’s favourite phrase, that I was the very thing he wished to see me; when, in an evil hour, he received my letter, containing my eloquent and detailed apology, for declining a place in the firm, and a desk and stool in the corner of the dark counting-house in Crane Alley, surmounting in height those of Owen, and the other clerks, and only inferior to the tripod of my father himself. All was wrong from that moment. Dubourg’s reports became as suspicious as if his bills had been noted for dishonour. I was summoned home in all haste, and received in the manner I have already communicated to you.

CHAPTER II

I begin shrewdly to suspect the young man of a terrible taint—Poetry; with which idle disease if he be infected, there’s no hope of him in a state course. Actum est of him for a commonwealth’s man, if he go to’t in rhyme once.

Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair

MY father had, generally speaking, his temper under complete self-command, and his anger rarely indicated itself by words, except in a sort of dry testy manner, to those who had displeased him. He never used threats, or expressions of loud resentment. All was arranged with him on system, and it was his practice to do ‘the needful’ on every occasion, without wasting words about it. It was, therefore, with a bitter smile that he listened to my imperfect answers concerning the state of commerce in France, and unmercifully permitted me to involve myself deeper and deeper in the mysteries of agio, tariffs, tare and tret; nor can I charge my memory with his having looked positively angry, until he found me unable to explain the exact effect which the depreciation of the louis d’or had produced on the negotiation of bills of exchange. ‘The most remarkable national occurrence in my time,’ said my father, (who nevertheless had seen the Revolution), ‘and he knows no more of it than a post on the quay!’

‘Mr. Francis,’ suggested Owen, in his timid and conciliatory manner, ‘cannot have forgotten, that by an arret of the King of France, dated 1st May, 1700, it was provided that the porteur, within ten days after due, must make demand——’

‘Mr. Francis,’ said my father, interrupting him, ‘will, I dare say, recollect for the moment any thing you are so kind as hint to him.—But, body o’ me! how Dubourg could permit him!—Hark ye, Owen, what sort of a youth is Clement Dubourg, his nephew there, in the office, the black-haired lad?’

‘One of the cleverest clerks, sir, in the house; a prodigious young man for his time,’ answered Owen; for the gaiety and civility of the young Frenchman had won his heart.

‘Ay, ay, I suppose he knows something of the nature of exchange. Dubourg was determined I should have one youngster at least about my hand who understood business; but I see his drift, and he shall find that I do so when he looks at the balance-sheet. Owen, let Clement’s salary be paid up to next quarter-day, and let him ship himself back to Bourdeaux in his father’s ship, which is clearing out yonder.’

‘Dismiss Clement Dubourg, sir?’ said Owen, with a faltering voice.

‘Yes, sir, dismiss him instantly; it is enough to have a stupid Englishman in the counting-house to make blunders, without keeping a sharp Frenchman there to profit by them.’

I had lived long enough in the territories of the Grand Monarque to contract a hearty aversion to arbitrary exertion of authority, even if it had not been instilled into me with my earliest breeding; and I could not refrain from interposing, to prevent an innocent and meritorious young man from paying the penalty of having acquired that proficiency which my father had desired for me.

‘I beg pardon, sir,’ when Mr. Osbaldistone had done speaking, ‘but I think it but just, that if I have been negligent of my studies, I should pay the forfeit myself. I have no reason to charge Monsieur Dubourg with having neglected to give me opportunities of improvement, however little I may have profited by them; and, with respect to Monsieur Clement Dubourg——’

‘With respect to him, and to you, I shall take the measures which I see needful,’ replied my father; ‘but it is fair in you, Frank, to take your own blame on your own shoulders—very fair, that cannot be denied.—I cannot acquit old Dubourg,’ he said, looking to Owen, ‘for having merely afforded Frank the means of useful knowledge, without either seeing that he took advantage of them, or reporting to me if he did not. You see, Owen, he has natural notions of equity becoming a British merchant.’

‘Mr. Francis,’ said the head clerk, with his usual formal inclination of the head, and a slight elevation of his right hand, which he had acquired by a habit of sticking his pen behind his ear before he spoke—‘Mr. Francis seems to understand the fundamental principle of all moral accounting, the great ethic rule of three. Let A do to B, as he would have B do to him; the product will give the rule of conduct required.’

My father smiled at this reduction of the golden rule to arithmetical form, but instantly proceeded.

‘All this signifies nothing, Frank; you have been throwing away your time like a boy, and in future you must learn to live like a man. I shall put you under Owen’s care for a few months, to recover the lost ground.’

I was about to reply, but Owen looked at me with such a supplicatory and warning gesture, that I was involuntarily silent.

‘We will then,’ continued my father, ‘resume the subject of mine of the 1st ultimo, to which you sent me an answer which was unadvised and unsatisfactory. So now, fill your glass, and push the bottle to Owen.’

Want of courage—of audacity, if you will—was never my failing. I answered firmly, ‘I was sorry that my letter was unsatisfactory, unadvised it was not; for I had given the proposal his goodness had made me my instant and anxious attention, and it was with no small pain that I found myself obliged to decline it.’

My father bent his keen eye for a moment on me, and instantly withdrew it. As he made no answer, I thought myself obliged to proceed, though with some hesitation, and he only interrupted me by monosyllables.

‘It is impossible, sir, for me to have higher respect for any character than I have for the commercial, even were it not yours.’

‘Indeed!’

‘It connects nation with nation, relieves the wants, and contributes to the wealth of all; and is to the general commonwealth of the civilized world what the daily intercourse of ordinary life is to private society, or rather, what air and food are to our bodies.’

‘Well, sir?’

‘And yet, sir, I find myself compelled to persist in declining to adopt a character which I am so ill qualified to support.’

‘I will take care that you acquire the qualifications necessary. You are no longer the guest and pupil of Dubourg.’

‘But, my dear sir, it is no defect of teaching which I plead, but my own inability to profit by instruction.’

‘Nonsense; have you kept your journal in the terms I desired?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Be pleased to bring it here.’

The volume thus required was a sort of commonplace book, kept by my father’s recommendation, in which I had been directed to enter notes of the miscellaneous information which I had acquired in the course of my studies. Foreseeing that he would demand inspection of this record, I had been attentive to transcribe such particulars of information as he would most likely be pleased with, but too often the pen had discharged the task without much correspondence with the head. And it had also happened, that, the book being the receptacle nearest to my hand, I had occasionally jotted down memoranda which had little regard to traffic. I now put it into my father’s hand, devoutly hoping he might light on nothing that would increase his displeasure against me. Owen’s face, which had looked something blank when the question was put, cleared up at my ready answer, and wore a smile of hope, when I brought from my apartment, and placed before my father, a commercial-looking volume, rather broader than it was long, having brazen clasps and a binding of rough calf. This looked business-like, and was encouraging to my benevolent well-wisher. But he actually smiled with pleasure as he heard my father run over some part of the contents, muttering his critical remarks as he went on.

‘Brandies—Barils and barricants, also tonneaux.—At Nantz 29—Velles to the barique at Cognac and Rochelle 27—At Bourdeaux 32—Very right, Frank—Duties on tonnage and custom-house, see Saxby’s Tables—That’s not well; you should have transcribed the passage; it fixes the thing in the memory—Reports outward and inward—Corn debentures—Over-sea Cockets—Linens—Isingham—Gentish—Stock-fish—Titling—Cropling—Lub-fish. You should have noted that they are all, nevertheless, to be entered as tidings.—How many inches long is a titling?’

Owen, seeing me at fault, hazarded a whisper, of which I fortunately caught the import.

‘Eighteen inches, sir——’

‘And a lub-fish is twenty-four—very right. It is important to remember this, on account of the Portuguese trade.—But what have we here?—Bourdeaux founded in the year— Castle of the Trompette—Palace of Gallienus—Well, well, that’s very right too.—This is a kind of waste-book, Owen, in which all the transactions of the day, emptions, orders, payments, receipts, acceptances, draughts, commissions, and advices, are entered miscellaneously.’

‘That they may be regularly transferred to the day-book and ledger,’ answered Owen; ‘I am glad Mr. Francis is so methodical.’

I perceived myself getting so fast into favour, that I began to fear the consequence would be my father’s more obstinate perseverance in his resolution that I must become a merchant; and, as I was determined on the contrary, I began to wish I had not, to use my friend Mr. Owen’s phrase, been so methodical. But I had no reason for apprehension on that score; for a blotted piece of paper dropped out of the book, and, being taken up by my father, he interrupted a hint from Owen, on the propriety of securing loose memoranda with a little paste, by exclaiming, ‘To the memory of Edward the Black Prince—What’s all this?—verses!—By Heaven, Frank, you are a greater blockhead than I supposed you!’

My father, you must recollect, as a man of business, looked upon the labour of poets with contempt; and as a religious man, and of the dissenting persuasion, he considered all such pursuits as equally trivial and profane. Before you condemn him, you must recall to remembrance how too many of the poets in the end of the seventeenth century had led their lives and employed their talents. The sect also to which my father belonged, felt, or perhaps affected, a puritanical aversion to the lighter exertions of literature. So that many causes contributed to augment the unpleasant surprise occasioned by the ill-timed discovery of this unfortunate copy of verses. As for poor Owen, could the bob-wig which he then wore have uncurled itself, and stood on end with horror, I am convinced the morning’s labour of the friseur would have been undone, merely by the excess of his astonishment at this enormity. An inroad on the strong-box, or an erasure in the ledger, or a missummation in a fitted account, could hardly have surprised him more disagreebly. My father read the lines sometimes with an affection of not being able to understand the sense,—sometimes in a mouthing tone of mock heroic,—always with an emphasis of the most bitter irony, most irritating to the nerves of an author.

‘“O for the voice of that wild horn,

On Fontarabian echoes borne,

The dying hero’s call,

That told imperial Charlemagne,

How Paynim sons of swarthy Spain

Had wrought his champion’s fall.”

‘Fontarabian echoes!’ continued my father, interrupting himself; ‘the Fontarabian Fair would have been more to the purpose.—Paynim?—What’s Paynim?—Could you not say Pagan as well, and write English, at least, if you must needs write nonsense?—

‘ “Sad over earth and ocean sounding,

And England’s distant cliffs astounding,

Such are the notes should say

How Britain’s hope, and France’s fear,

Victor of Cressy and Poitier,

In Bourdeaux dying lay.”

‘Poitiers, by the way, is always spelt with an s, and I know no reason why orthography should give place to rhyme.—

‘ “Raise my faint head, my squires,” he said,

“And let the casement be displayed,

That I may see once more

The splendour of the setting sun

Gleam on thy mirror’d wave, Garonne,

And Blaye’s empurpled shore.”

‘Garonne and sun is a bad rhyme. Why, Frank, you do not even understand the beggarly trade you have chosen.

‘“Like me, he sinks to Glory’s sleep,

His fall the dews of evening steep,

As if in sorrow shed.

So soft shall fall the trickling tear,

When England’s maids and matrons hear

Of their Black Edward dead.”

‘“And though my sun of glory set,

Nor France, nor England shall forget

The terror of my name;

And oft shall Britain’s heroes rise,

New planets in these southern skies,

Through clouds of blood and flame.”

A cloud of flame is something new—Good-morrow, my masters all, and a merry Christmas to you!—Why, the bellman writes better lines.’ He then tossed the paper from him with an air of superlative contempt, and concluded,— ‘Upon my credit, Frank, you are a greater blockhead than I took you for.’

What could I say, my dear Tresham?—There I stood, swelling with indignant mo

rtification, while my father regarded me with a calm but stern look of scorn and pity; and poor Owen, with uplifted hands and eyes, looked as striking a picture of horror as if he had just read his patron’s name in the Gazette. At length I took courage to speak, endeavouring that my tone of voice should betray my feelings as little as possible.

‘I am quite aware, sir, how ill qualified I am to play the conspicuous part in society you have destined for me; and luckily, I am not ambitious of the wealth I might acquire. Mr. Owen would make a much more effective assistant.’ I said this in some malice, for I considered Owen as having deserted my cause a little too soon.

Ivanhoe: A Romance

Ivanhoe: A Romance Old Mortality, Complete

Old Mortality, Complete The Pirate

The Pirate Kenilworth

Kenilworth The Black Dwarf

The Black Dwarf A Legend of Montrose

A Legend of Montrose The Monastery

The Monastery The Bride of Lammermoor

The Bride of Lammermoor Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century

Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century St. Ronan's Well

St. Ronan's Well The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day

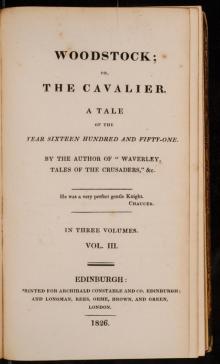

The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day Woodstock; or, the Cavalier

Woodstock; or, the Cavalier_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2) Peveril of the Peak

Peveril of the Peak Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since Old Mortality, Volume 1.

Old Mortality, Volume 1. Waverley Novels — Volume 12

Waverley Novels — Volume 12 The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete Quentin Durward

Quentin Durward Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete

Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete

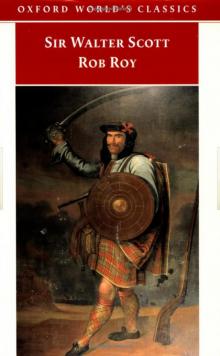

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete Rob Roy — Complete

Rob Roy — Complete The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2) The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1 Rob Roy — Volume 01

Rob Roy — Volume 01 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01 The Talisman toc-2

The Talisman toc-2 Rob Roy

Rob Roy Old Mortality, Volume 2.

Old Mortality, Volume 2. The Betrothed

The Betrothed Waverley

Waverley The Surgeon's Daughter

The Surgeon's Daughter Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Antiquary

The Antiquary Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft

Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft Trial of Duncan Terig

Trial of Duncan Terig Redgauntlet

Redgauntlet My Aunt Margaret's Mirror

My Aunt Margaret's Mirror Guy Mannering or The Astrologer

Guy Mannering or The Astrologer Marmion

Marmion The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock

The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock Chronicles of the Canongate

Chronicles of the Canongate The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day

The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day The Heart of Mid-Lothian

The Heart of Mid-Lothian Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake