- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Ivanhoe: A Romance

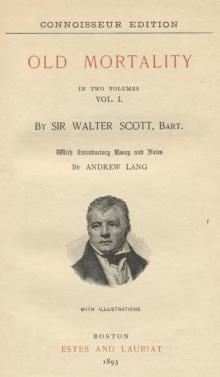

Ivanhoe: A Romance Old Mortality, Complete

Old Mortality, Complete The Pirate

The Pirate Kenilworth

Kenilworth The Black Dwarf

The Black Dwarf A Legend of Montrose

A Legend of Montrose The Monastery

The Monastery The Bride of Lammermoor

The Bride of Lammermoor Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century

Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century St. Ronan's Well

St. Ronan's Well The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day

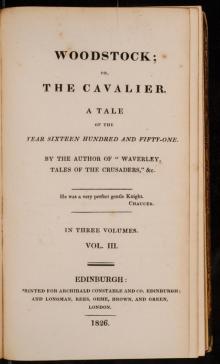

The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day Woodstock; or, the Cavalier

Woodstock; or, the Cavalier_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2) Peveril of the Peak

Peveril of the Peak Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since Old Mortality, Volume 1.

Old Mortality, Volume 1. Waverley Novels — Volume 12

Waverley Novels — Volume 12 The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete Quentin Durward

Quentin Durward Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete

Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete Rob Roy — Complete

Rob Roy — Complete The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2) The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1 Rob Roy — Volume 01

Rob Roy — Volume 01 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01 The Talisman toc-2

The Talisman toc-2 Rob Roy

Rob Roy Old Mortality, Volume 2.

Old Mortality, Volume 2. The Betrothed

The Betrothed Waverley

Waverley The Surgeon's Daughter

The Surgeon's Daughter Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Antiquary

The Antiquary Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft

Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft Trial of Duncan Terig

Trial of Duncan Terig Redgauntlet

Redgauntlet My Aunt Margaret's Mirror

My Aunt Margaret's Mirror Guy Mannering or The Astrologer

Guy Mannering or The Astrologer Marmion

Marmion The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock

The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock Chronicles of the Canongate

Chronicles of the Canongate The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day

The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day The Heart of Mid-Lothian

The Heart of Mid-Lothian Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake