- Home

- Walter Scott

Lady of the Lake Page 3

Lady of the Lake Read online

Page 3

The great Reform Bill was being discussed throughout Scotland, menacing what were really abuses, but what Scott, with his intense conservatism, believed to be sacred and inviolable institutions. The dying man roused himself to make a stand against the abominable bill. In a speech which he made at Jedburgh, he was hissed and hooted by the crowd, and he left the town with the dastardly cry of "Burk Sir Walter!" ringing in his ears.

Nature now intervened to ease the intolerable strain. Scott's anxiety concerning his debt gradually gave way to an hallucination that it had all been paid. His friends took advantage of the quietude which followed to induce him to make the journey to Italy, in the fear that the severe winter of Scotland would prove fatal. A ship of His Majesty's fleet was put at his disposal, and he set sail for Malta. The youthful adventurousness of the man flared up again oddly for a moment, when he insisted on being set ashore upon a volcanic island in the Mediterranean which had appeared but a few days before and which sank beneath the surface shortly after. The climate of Malta at first appeared to benefit him; but when he heard, one day, of the death of Goethe at Weimar, he seemed seized with a sudden apprehension of his own end, and insisted upon hurrying back through Europe, in order that he might look once more on Abbotsford. On the ride from Edinburgh he remained for the first two stages entirely unconscious. But as the carriage entered the valley of the Gala he opened his eyes and murmured the name of objects as they passed, "Gala water, surely—Buckholm—Torwoodlee." When the towers of Abbotsford came in view, he was so filled with delight that he could scarcely be restrained from leaping out. At the gates he greeted faithful Laidlaw in a voice strong and hearty as of old: "Why, man, how often I have thought of you!" and smiled and wept over the dogs who came rushing as in bygone times to lick his hand. He died a few days later, on the afternoon of a glorious autumn day, with all the windows open, so that he might catch to the last the whisper of the Tweed over its pebbles.

"And so," says Carlyle, "the curtain falls; and the strong Walter Scott is with us no more. A possession from him does remain; widely scattered; yet attainable; not inconsiderable. It can be said of him, when he departed, he took a Man's life along with him. No sounder piece of British manhood was put together in that eighteenth century of Time. Alas, his fine Scotch face, with its shaggy honesty, sagacity and goodness, when we saw it latterly on the Edinburgh streets, was all worn with care, the joy all fled from it—plowed deep with labor and sorrow. We shall never forget it; we shall never see it again. Adieu, Sir Walter, pride of all Scotchmen, take our proud and sad farewell."

FOOTNOTES:

[1] See Scott's ballad "The Eve of St. John."

[2] Asked.

[3] Bested, got the better of.

II. SCOTT'S PLACE IN THE ROMANTIC MOVEMENT

In order rightly to appreciate the poetry of Scott it is necessary to understand something of that remarkable "Romantic Movement" which took place toward the end of the eighteenth century, and within a space of twenty-five years completely changed the face of English literature. Both the causes and the effects of this movement were much more than merely literary; the "romantic revival" penetrated every crevice and ramification of life in those parts of Europe which it affected; its social, political, and religious results were all deeply significant. But we must here confine ourselves to such aspects of the revival as showed themselves in English poetry.

Eighteenth century poetry had been distinguished by its polish, its formal correctness, or—to use a term in much favor with critics of that day—its "elegance." The various and wayward metrical effects of the Elizabethan and Jacobean poets had been discarded for a few well-recognized verse forms, which themselves in turn had become still further limited by the application to them of precise rules of structure. Hand in hand with this restricting process in meter, had gone a similar tendency in diction. The simple, concrete phrases of daily speech had given way to stately periphrases; the rich and riotous vocabulary of earlier poetry had been replaced by one more decorous, measured, and high-sounding. A corresponding process of selection and exclusion was applied to the subject matter of poetry. Passion, lyric exaltation, delight in the concrete life of man and nature, passed out of fashion; in their stead came social satire, criticism, generalized observation. While the classical influence, as it is usually called, was at its height, with such men as Dryden and Pope to exemplify it, it did a great work; but toward the end of the eighth decade of the eighteenth century it had visibly run to seed. The feeble Hayley, the silly Della Crusca, the arid Erasmus Darwin, were its only exemplars. England was ripe for a literary revolution, a return to nature and to passion; and such a revolution was not slow in coming.

It announced itself first in George Crabbe, who turned to paint the life of the poor with patient realism; in Burns, who poured out in his songs the passion of love, the passion of sorrow, the passion of conviviality; in Blake, who tried to reach across the horizon of visible fact to mystical heavens of more enduring reality. Following close upon these men came the four poets destined to accomplish the revolution which the early comers had begun. They were born within four years of each other, Wordsworth in 1770, Scott in 1771, Coleridge in 1772, Southey in 1774. As we look at these four men now, and estimate their worth as poets, we see that Southey drops almost out of the account, and that Wordsworth and Coleridge stand, so far as the highest qualities of poetry go, far above Scott, as, indeed, Blake and Burns do also. But the contemporary judgment upon them was directly the reverse; and Scott's poetry exercised an influence over his age immeasurably greater than that of any of the other three. Let us attempt to discover what qualities this poetry possessed which gave it its astonishing hold upon the age when it was written. In so doing, we may discover indirectly some of the reasons why it still retains a large portion of its popularity, and perhaps arrive at some grounds of judgment by which we may test its right thereto.

One reason why Scott's poetry was immediately welcomed, while that of Wordsworth and of Coleridge lay neglected, is to be found in the fact that in the matter of diction Scott was much less revolutionary than they. By nature and education he was conservative; he put The Lay of the Last Minstrel into the mouth of a rude harper of the North in order to shield himself from the charge of "attempting to set up a new school in poetry," and he never throughout his life violated the conventions, literary or social, if he could possibly avoid doing so. This bias toward conservatism and conventionality shows itself particularly in the language of his poems. He was compelled, of course, to use much more concrete and vivid terms than the eighteenth century poets had used, because he was dealing with much more concrete and vivid matter; but his language, nevertheless, has a prevailing stateliness, and at times an artificiality, which recommended it to readers tired of the inanities of Hayley and Mason, but unwilling to accept the startling simplicity and concreteness of diction exemplified by the Lake poets at their best.

Another peculiarity of Scott's poetry which made powerfully for its popularity, was its spirited meter. People were weary of the heroic couplet, and turned eagerly to these hurried verses, that went on their way with the sharp tramp of moss-troopers, and heated the blood like a drum. The meters of Coleridge, subtle, delicate, and poignant, had been passed by with indifference—had not been heard perhaps, for lack of ears trained to hear; but Scott's metrical effects were such as a child could appreciate, and a soldier could carry in his head.

Analogous to this treatment of meter, though belonging to a less formal side of his art, was Scott's treatment of nature, the landscape setting of his stories. Perhaps the most obvious feature of the romantic revival was a reawakening of interest in out-door nature. It was as if for a hundred years past people had been stricken blind as soon as they passed from the city streets into the country. A trim garden, an artfully placed country house, a well-kept preserve, they might see; but for the great shaggy world of mountain and sea—it had been shut out of man's elegant vision. Before Scott began to write there had been no lack of pro

phets of the new nature-worship, but none of them of a sort to catch the general ear. Wordsworth's pantheism was too mystical, too delicate and intuitive, to recommend itself to any but chosen spirits; Crabbe's descriptions were too minute, Coleridge's too intense, to please. Scott was the first to paint nature with a broad, free touch, without raptures or philosophizing, but with a healthy pleasure in its obvious beauties, such as appeal to average men. His "scenery" seldom exists for its own sake, but serves, as it should, for background and setting of his story. As his readers followed the fortunes of William of Deloraine or Roderick Dhu, they traversed by sunlight and by moonlight landscapes of wild romantic charm, and felt their beauty quite naturally, as a part of the excitement of that wild life. They felt it the more readily because of a touch of artificial stateliness in the handling, a slight theatrical heightening of effect—from an absolute point of view a defect, but highly congenial to the taste of the time. It was the scenic side of nature which Scott gave, and gave inimitably, while Burns was piercing to the inner heart of her tenderness in his lines "To a Mountain Daisy" and "To a Mouse," while Wordsworth was mystically communing with her soul, in his "Tintern Abbey." It was the scenic side of nature for which the perceptions of men were ripe; so they left profounder poets to their musings, and followed after the poet who could give them a brilliant story set in a brilliant scene.

Again, the emotional key to Scott's poetry was on a comprehensible plane. The situations with which he deals, the passions, ambitions, satisfactions, which he portrays, belong, in one form or another, to all men, or at least are easily grasped by the imaginations of all men. It has often been said that Scott is the most Homeric of English poets; so far as the claim rests on considerations of style, it is hardly to be granted, for nothing could be farther than the hurrying torrent of Scott's verse from the "long and refluent music" of Homer. But in this other respect, that he deals in the rudimentary stuff of human character in a straightforward way, without a hint of modern complexities and super-subtleties, he is really akin to the master poet of antiquity. This, added to the crude wild life which he pictures, the vigorous sweep of his action, the sincere glow of romance which bathes his story—all so tonic in their effect upon minds long used to the stuffy decorum of didactic poetry, completed the triumph of The Lay of the Last Minstrel, Marmion, and The Lady of the Lake, over their age.

As has been already suggested, Scott cannot be put in the first rank of poets. No compromise can be made on this point, because upon it the whole theory of poetry depends. Neither on the formal nor on the essential sides of his art is he among the small company of the supreme. And no one understood this better than himself. He touched the keynote of his own power, though with too great modesty, when he said, "I am sensible that if there is anything good about my poetry ... it is a hurried frankness of composition which pleases soldiers, sailors, and young people of bold and active dispositions." The poet Campbell, who was so fascinated by Scott's ballad of "Cadyow Castle" that he used to repeat it aloud on the North Bridge of Edinburgh until "the whole fraternity of coachmen knew him by tongue as he passed," characterizes the predominant charm of Scott's poetry as lying in a "strong, pithy eloquence," which is perhaps only another name for "hurried frankness of composition." If this is not the highest quality to which poetry can attain, it is a very admirable one; and it will be a sad day for the English-speaking race when there shall not be found persons of every age and walk of life, to take the same delights in these stirring poems as their author loved to think was taken by "soldiers, sailors, and young people of bold and active dispositions."

III. THE LADY OF THE LAKE

1. HISTORICAL SETTING

The Lady of the Lake deals with a distinct epoch in the life of King James V of Scotland, and has lying back of it a considerable amount of historical fact, an understanding of which will help in the appreciation of the poem. During his minority the King was under the tutelage of Archibald Douglas, sixth Earl of Angus, who had married the King's mother. The young monarch chafed for a long time under this authority, but the Douglases were so powerful that he was unable to shake it off, in spite of several desperate attempts on the part of his sympathizers to rescue him. In 1528 the King, then sixteen years of age, escaped from his own castle of Falkland to Stirling Castle. The governor of Stirling, an enemy of the Douglas family, received him joyfully. There soon gathered about his standard a sufficient number of powerful peers to enable him to depose the Earl of Angus from the regency and to banish him and all his family to England. The Douglas who figures in the poem is an imaginary uncle of the banished regent, and himself under the ban, compelled to hide away in the shelter provided for him by Roderick Dhu on the lonely island in Loch Katrine. He is represented as having been loved and trusted by King James during the boyhood of the latter, before the enmity sprang up between the house of Angus and the throne. This enmity, to quote from the History of the House of Douglas, published at Edinburgh in 1743, "was so inveterate, that numerous as their allies were, their nearest friends, even in the most remote parts of Scotland, durst not entertain them, unless under the strictest and closest disguise."

The outlawed border chieftain, Roderick Dhu, who gives shelter to the persecuted Douglas, is a fictitious character, but one entirely typical of the time and place. The expedition undertaken by the young King against the Border clans, under the guise of a hunting party, is in part, at least, historic. Pitscottie's History says: "In 1529 James V made a convention at Edinburgh for the purpose of considering the best mode of quelling the Border robbers, who, during the license of his minority and the troubles which followed, had committed many exorbitances. Accordingly, he assembled a flying army of ten thousand men, consisting of his principal nobility and their followers, who were directed to bring their hawks and dogs with them, that the monarch might refresh himself with sport during the intervals of military execution. With this array he swept through Ettrick forest, where he hanged over the gate of his own castle Piers Cockburn of Henderland, who had prepared, according to tradition, a feast for his reception."

2. GENERAL CRITICISM AND ANALYSIS

The Lady of the Lake appeared in 1810. Two years before, Marmion had vastly increased the popular enthusiasm aroused by The Lay of the Last Minstrel, and the success of his second long poem had so exhilarated Scott that, as he says, he "felt equal to anything and everything." To one of his kinswomen, who urged him not to jeopardize his fame by another effort in the same kind, he gaily quoted the words of Montrose:

He either fears his fate too much Or his deserts are small, Who dares not put it to the touch, To win or lose it all.

The result justified his confidence; for not only was The Lady of the Lake as successful as its predecessors, but it remains the most sterling of Scott's poems. The somewhat cheap supernaturalism of the Lay appears in it only for a moment; both the story and the characters are of a less theatrical type than in Marmion; and it has a glow, animation, and onset, which was denied to the later poems, Rokeby and The Lord of the Isles.

The following outline abridged from the excellent one given by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review for August, 1810, will be useful as a basis for criticism of the matter and style of the poem.

"The first canto begins with a description of a staghunt in the Highlands of Perthshire. As the chase lengthens, the sportsmen drop off; till at last the foremost horseman is left alone; and his horse, overcome with fatigue, stumbles and dies. The adventurer, climbing up a craggy eminence, discovers Loch Katrine spread out in evening glory before him. The huntsman winds his horn; and sees, to his infinite surprise, a little skiff, guided by a lovely woman, glide from beneath the trees that overhang the water, and approach the shore at his feet. Upon the stranger's approach, she pushes the shallop from the shore in alarm. After a short parley, however, she carries him to a woody island, where she leads him into a sort of silvan mansion, rudely constructed, and hung round with trophies of war and the chase. An elderly lady is introduced at supper; and

the stranger, after disclosing himself to be 'James Fitz-James, the knight of Snowdoun,' tries in vain to discover the name and history of the ladies.

"The second canto opens with a picture of the aged harper, Allan-bane, sitting on the island beach with the damsel, watching the skiff which carries the stranger back to land. A conversation ensues, from which the reader gathers that the lady is a daughter of the Douglas, who, being exiled by royal displeasure from court, had accepted this asylum from Sir Roderick Dhu, a Highland chieftain long outlawed for deeds of blood; that this dark chief is in love with his fair protégée, but that her affections are engaged to Malcolm Graeme, a younger and more amiable mountaineer. The sound of distant music is heard on the lake; and the barges of Sir Roderick are discovered, proceeding in triumph to the island. Ellen, hearing her father's horn at that instant on the opposite shore, flies to meet him and Malcolm Graeme, who is received with cold and stately civility by the lord of the isle. Sir Roderick informs the Douglas that his retreat has been discovered, and that the King (James V), under pretence of hunting, has assembled a large force in the neighborhood. He then proposes impetuously that they should unite their fortunes by his marriage with Ellen, and rouse the whole Western Highlands. The Douglas, intimating that his daughter has repugnances which she cannot overcome, declares that he will retire to a cave in the neighboring mountains until the issue of the King's threat is seen. The heart of Roderick is wrung with agony at this rejection; and when Malcolm advances to Ellen, he pushes him violently back—and a scuffle ensues, which is with difficulty appeased by the giant arm of Douglas. Malcolm then withdraws in proud resentment, plunges into the water, and swims over by moonlight to the mainland.

Ivanhoe: A Romance

Ivanhoe: A Romance Old Mortality, Complete

Old Mortality, Complete The Pirate

The Pirate Kenilworth

Kenilworth The Black Dwarf

The Black Dwarf A Legend of Montrose

A Legend of Montrose The Monastery

The Monastery The Bride of Lammermoor

The Bride of Lammermoor Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century

Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century St. Ronan's Well

St. Ronan's Well The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day

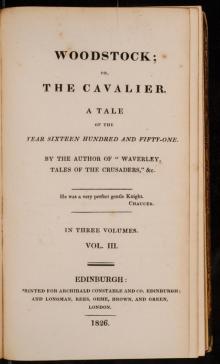

The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day Woodstock; or, the Cavalier

Woodstock; or, the Cavalier_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2) Peveril of the Peak

Peveril of the Peak Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since Old Mortality, Volume 1.

Old Mortality, Volume 1. Waverley Novels — Volume 12

Waverley Novels — Volume 12 The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete Quentin Durward

Quentin Durward Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete

Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete Rob Roy — Complete

Rob Roy — Complete The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2) The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1 Rob Roy — Volume 01

Rob Roy — Volume 01 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01 The Talisman toc-2

The Talisman toc-2 Rob Roy

Rob Roy Old Mortality, Volume 2.

Old Mortality, Volume 2. The Betrothed

The Betrothed Waverley

Waverley The Surgeon's Daughter

The Surgeon's Daughter Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Antiquary

The Antiquary Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft

Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft Trial of Duncan Terig

Trial of Duncan Terig Redgauntlet

Redgauntlet My Aunt Margaret's Mirror

My Aunt Margaret's Mirror Guy Mannering or The Astrologer

Guy Mannering or The Astrologer Marmion

Marmion The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock

The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock Chronicles of the Canongate

Chronicles of the Canongate The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day

The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day The Heart of Mid-Lothian

The Heart of Mid-Lothian Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake