- Home

- Walter Scott

The Betrothed Page 34

The Betrothed Read online

Page 34

"One who betrayeth a trust reposed—a betrayer," said the interpreter. The phrase which he used recalled to Eveline's memory her boding vision or dream. "Alas!" she said, "the vengeance of the fiend is about to be accomplished. Widow'd wife and wedded maid—these epithets have long been mine. Betrothed!—wo's me! it is the key-stone of my destiny. Betrayer I am now denounced, though, thank God, I am clear from the guilt! It only follows that I should be betrayed, and the evil prophecy will be fulfilled to the very letter." fir?

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-NINTH

Out on ye, owls;

Nothing but songs of death?

RICHARD III.

More than three months had elapsed since the event narrated in the last chapter, and it had been the precursor of others of still greater importance, which will evolve themselves in the course of our narrative. But, profess to present to the reader not a precise detail of circumstances, according to their order and date, but a series of pictures, endeavouring to exhibit the most striking incidents before the eye or imagination of those whom it may concern, we therefore open a new scene, and bring other actors upon the stage.

Along a wasted tract of country, more than twelve miles distant from the Garde Doloureuse, in the heat of a summer noon, which shed a burning lustre on the silent valley, and the blackened ruins of the cottages with which it had been once graced, two travellers walked slowly, whose palmer cloaks, pilgrims' staves, large slouched hats, with a scallop shell bound on the front of each, above all, the cross, cut in red cloth upon their shoulders, marked them as pilgrims who had accomplished their vow, and had returned from that fatal bourne, from which, in those days, returned so few of the thousands who visited it, whether in the love of enterprise, or in the ardour of devotion.

The pilgrims had passed, that morning, through a scene of devastation similar to, and scarce surpassed in misery by, those which they had often trod during the wars of the Cross. They had seen hamlets which appeared to have suffered all the fury of military execution, the houses being burned to the ground; and in many cases the carcasses of the miserable inhabitants, or rather relics of such objects, were suspended on temporary gibbets, or on the trees, which had been allowed to remain standing, only, it would seem, to serve the convenience of the executioners. Living creatures they saw none, excepting those wild denizens of nature who seemed silently resuming the now wasted district, from which they might have been formerly expelled by the course of civilization. Their ears were no less disagreeably occupied than their eyes. The pensive travellers might indeed hear the screams of the raven, as if lamenting the decay of the carnage on which he had been gorged; and now and then the plaintive howl of some dog, deprived of his home and master; but no sounds which argued either labour or domestication of any kind.

The sable figures, who, with wearied steps, as it appeared, travelled through these scenes of desolation and ravage, seemed assimilated to them in appearance. They spoke not with each other —they looked not to each other—but one, the shorter of the pair, keeping about half a pace in front of his companion, they moved slowly, as priests returning from a sinner's death-bed, or rather as spectres flitting along the precincts of a church-yard.

At length they reached a grassy mound, on the top of which was placed one of those receptacles for the dead of the ancient British chiefs of distinction, called Kist-vaen, which are composed of upright fragments of granite, so placed as to form a stone coffin, or something bearing that resemblance. The sepulchre had been long violated by the victorious Saxons, either in scorn or in idle curiosity, or because treasures were supposed to be sometimes concealed in such spots. The huge flat stone which had once been the cover of the coffin, if so it might be termed, lay broken in two pieces at some distance from the sepulchre; and, overgrown as the fragments were with grass and lichens, showed plainly that the lid had been removed to its present situation many years before. A stunted and doddered oak still spread its branches over the open and rude mausoleum, as if the Druid's badge and emblem, shattered and storm-broken, was still bending to offer its protection to the last remnants of their worship.

"This, then, is the Kist-vaen," said the shorter pilgrim; "and here we must abide tidings of our scout. But what, Philip Guarine, have we to expect as an explanation of the devastation which we have traversed?"

"Some incursion of the Welsh wolves, my lord," replied Guarine; "and, by Our Lady, here lies a poor Saxon sheep whom they have snapped up."

The Constable (for he was the pilgrim who had walked foremost) as he heard his squire speak, and saw the corpse of a man amongst the long grass; by which, indeed, it was so hidden, that he himself had passed without notice, what the esquire, in less abstracted mood, had not failed to observe. The leathern doublet of the slain bespoke him an English peasant—the body lay on its face, and the arrow which had caused his death still stuck in his back.

Philip Guarine, with the cool indifference of one accustomed to such scenes, drew the shaft from the man's back, as composedly as he would have removed it from the body of a deer. With similar indifference the Constable signed to his esquire to give him the arrow—looked at it with indolent curiosity, and then said, "Thou hast forgotten thy old craft, Guarine, when thou callest that a Welsh shaft. Trust me, it flew from a Norman bow; but why it should be found in the body of that English churl, I can ill guess."

"Some runaway serf, I would warrant—some mongrel cur, who had joined the Welsh pack of hounds," answered the esquire.

"It may be so," said the Constable; "but I rather augur some civil war among the Lords Marchers themselves. The Welsh, indeed, sweep the villages, and leave nothing behind them but blood and ashes, but here even castles seem to have been stormed and taken. May God send us good news of the Garde Doloureuse!"

"Amen!" replied his squire; "but if Renault Vidal brings it, 'twill be the first time he has proved a bird of good omen."

"Philip," said the Constable, "I have already told thee thou art a jealous-pated fool. How many times has Vidal shown his faith in doubt—his address in difficulty-his courage in battle-his patience under suffering?"

"It may be all very true, my lord," replied Guarine; "yet—but what avails to speak?—I own he has done you sometimes good service; but loath were I that your life or honour were at the mercy of Renault Vidal."

"In the name of all the saints, thou peevish and suspicious fool, what is it thou canst found upon to his prejudice?"

"Nothing, my lord," replied Guarine, "but instinctive suspicion and aversion. The child that, for the first time, sees a snake, knows nothing of its evil properties, yet he will not chase it and take it up as he would a butterfly. Such is my dislike of Vidal—I cannot help it. I could pardon the man his malicious and gloomy sidelong looks, when he thinks no one observes him; but his sneering laugh I cannot forgive—it is like the beast we heard of in Judea, who laughs, they say, before he tears and destroys."

"Philip," said De Lacy, "I am sorry for thee—sorry, from my soul, to see such a predominating and causeless jealousy occupy the brain of a gallant old soldier. Here, in this last misfortune, to recall no more ancient proofs of his fidelity, could he mean otherwise than well with us, when, thrown by shipwreck upon the coast of Wales, we would have been doomed to instant death, had the Cymri recognized in me the Constable of Chester, and in thee his trusty esquire, the executioner of his commands against the Welsh in so many instances?"

"I acknowledge," said Philip Guarine, "death had surely been our fortune, had not that man's ingenuity represented us as pilgrims, and, under that character, acted as our interpreter—and in that character he entirely precluded us from getting information from any one respecting the state of things here, which it behoved your lordship much to know, and which I must needs say looks gloomy and suspicious enough."

"Still art thou a fool, Guarine," said the Constable; "for, look you, had Vidal meant ill by us, why should he not have betrayed us to the Welsh, or suffered us, by showing such knowledge as thou and I may have of their

gibberish, to betray ourselves?'

"Well, my lord," said Guarine, "I may be silenced, but not satisfied. All the fair words he can speak—all the fine tunes he can play—Renault Vidal will be to my eyes ever a dark and suspicious man, with features always ready to mould themselves into the fittest form to attract confidence; with a tongue framed to utter the most flattering and agreeable words at one time, and at another to play shrewd plainness or blunt honesty; and an eye which, when he thinks himself unobserved, contradicts every assumed expression of features, every protestation of honesty, and every word of courtesy or cordiality to which his tongue has given utterance. But I speak not more on the subject; only I am an old mastiff, of the true breed—I love my master, but cannot endure some of those whom he favours; and yonder, as I judge, comes Vidal, to give us such an account of our situation as it shall please him."

A horseman was indeed seen advancing in the path towards the Kist- vaen, with a hasty pace; and his dress, in which something of the Eastern fashion was manifest, with the fantastic attire usually worn by men of his profession, made the Constable aware that the minstrel, of whom they were speaking, was rapidly approaching them.

Although Hugo de Lacy rendered this attendant no more than what in justice he supposed his services demanded, when he vindicated him from the suspicions thrown out by Guarine, yet at the bottom of his heart he had sometimes shared those suspicions, and was often angry at himself, as a just and honest man, for censuring, on the slight testimony of looks, and sometimes casual expressions, a fidelity which seemed to be proved by many acts of zeal and integrity.

When Vidal approached and dismounted to make his obeisance, his master hasted to speak to him in words of favour, as if conscious he had been partly sharing Guarine's unjust judgment upon him, by even listening to it. "Welcome, my trusty Vidal," he said; "thou hast been the raven that fed us on the mountains of Wales, be now the dove that brings us good tidings from the Marches.—Thou art silent. What mean these downcast looks—that embarrassed carriage—that cap plucked down o'er thine eyes?—In God's name, man, speak!—Fear not for me—I can bear worse than tongue of man may tell. Thou hast seen me in the wars of Palestine, when my brave followers fell, man by man, around me, and when I was left well-nigh alone—and did I blench then?—Thou hast seen me when the ship's keel lay grating on the rock, and the billows flew in foam over her deck—did I blench then?—No—nor will I now."

"Boast not," said the minstrel, looking fixedly upon the Constable, as the former assumed the port and countenance of one who sets Fortune and her utmost malice at defiance—"boast not, lest thy bands be made strong." There was a pause of a minute, during which the group formed at this instant a singular picture.

Afraid to ask, yet ashamed to _seem to fear the ill tidings which impended, the Constable confronted his messenger with person erect, arms folded, and brow expanded with resolution: while the minstrel, carried beyond his usual and guarded apathy by the interest of the moment, bent on his master a keen fixed glance, as if to observe whether his courage was real or assumed.

Philip Guarine, on the other hand, to whom Heaven, in assigning him a rough exterior, had denied neither sense nor observation, kept his eye in turn, firmly fixed on Vidal, as if endeavouring to determine what was the character of that deep interest which gleamed in the minstrel's looks apparently, and was unable to ascertain whether it was that of a faithful domestic sympathetically agitated by the bad news with which he was about to afflict his master, or that of an executioner standing with his knife suspended over his victim, deferring his blow until he should discover where it would be most sensibly felt. In Guarine's mind, prejudiced, perhaps, by the previous opinion he had entertained, the latter sentiment so decidedly predominated, that he longed to raise his staff, and strike down to the earth the servant, who seemed thus to enjoy the protracted sufferings of their common master.

At length a convulsive movement crossed the brow of the Constable, and Guarine, when he beheld a sardonic smile begin to curl Vidal's lip, could keep silence no longer. "Vidal," he said, "thou art a—"

"A bearer of bad tidings," said Vidal, interrupting him, "therefore subject to the misconstruction of every fool who cannot distinguish between the author of harm, and him who unwillingly reports it."

"To what purpose this delay?" said the Constable. "Come, Sir Minstrel, I will spare you a pang—Eveline has forsaken and forgotten me?" The minstrel assented by a low inclination.

Hugo de Lacy paced a short turn before the stone monument, endeavouring to conquer the deep emotion which he felt. "I forgive her," he said. "Forgive, did I say—Alas! I have nothing to forgive. She used but the right I left in her hand—yes—our date of engagement was out—she had heard of my losses—my defeats—the destruction of my hopes—the expenditure of my wealth; and has taken the first opportunity which strict law afforded to break off her engagement with one bankrupt in fortune and fame. Many a maiden would have done—perhaps in prudence should have done— this;—but that woman's name should not have been Eveline Berenger."

He leaned on his esquire's arm, and for an instant laid his head on his shoulder with a depth of emotion which Guarine had never before seen him betray, and which, in awkward kindness, he could only attempt to console, by bidding his master "be of good courage—he had lost but a woman."

"This is no selfish emotion, Philip," said the Constable, resuming self-command. "I grieve less that she has left me, than that she has misjudged me—that she has treated me as the pawnbroker does his wretched creditor, who arrests the pledge as the very moment elapses within which it might have been relieved. Did she then think that I in my turn would have been a creditor so rigid?—that I, who, since I knew her, scarce deemed myself worthy of her when I had wealth and fame, should insist on her sharing my diminished and degraded fortunes? How little she ever knew me, or how selfish must she have supposed my misfortunes to have made me! But be it so—she is gone, and may she be happy. The thought that she disturbed me shall pass from my mind; and I will think she has done that which I myself, as her best friend, must in honour have advised."

So saying, his countenance, to the surprise of his attendants, resumed its usual firm composure.

"I give you joy," said the esquire, in a whisper to the minstrel; "your evil news have wounded less deeply than, doubtless, you believed was possible."

"Alas!" replied the minstrel, "I have others and worse behind." This answer was made in an equivocal tone of voice, corresponding to the peculiarity of his manner, and like that seeming emotion of a deep but very doubtful character.

"Eveline Berenger is then married," said the Constable; "and, let me make a wild guess,—she has not abandoned the family, though she has forsaken the individual—she is still a Lacy? ha?—Dolt that thou art, wilt thou not understand me? She is married to Damian de Lacy—to my nephew?"

The effort with which the Constable gave breath to this supposition formed a strange contrast to the constrained smile to which he compelled his features while he uttered it. With such a smile a man about to drink poison might name a health, as he put the fatal beverage to his lips. "No, my lord—not married," answered the minstrel, with an emphasis on the word, which the Constable knew how to interpret.

"No, no," he replied quickly, "not married, perhaps, but engaged- troth-plighted. Wherefore not? The date of her old alliance was out, why not enter into a new engagement?"

"The Lady Eveline and Sir Damian de Lacy are not affianced that I know of," answered his attendant.

This reply drove De Lacy's patience to extremity.

"Dog! dost thou trifle with me?" he exclaimed: "Vile wire-pincher, thou torturest me! Speak the worst at once, or I will presently make thee minstrel to the household of Satan."

Calm and collected did the minstrel reply,—"The Lady Eveline and Sir Damian are neither married nor affianced, my lord. They have loved and lived together—par amours."

"Dog, and son of a dog," said De Lacy, "thou liest!" And, seizing the m

instrel by the breast, the exasperated baron shook him with his whole strength. But great as that strength was, it was unable to stagger Vidal, a practised wrestler, in the firm posture which he had assumed, any more than his master's wrath could disturb the composure of the minstrel's bearing.

"Confess thou hast lied," said the Constable, releasing him, after having effected by his violence no greater degree of agitation than the exertion of human force produces upon the Rocking Stones of the Druids, which may be shaken, indeed, but not displaced.

"Were a lie to buy my own life, yea, the lives of all my tribe," said the minstrel, "I would not tell one. But truth itself is ever termed falsehood when it counteracts the train of our passions."

"Hear him, Philip Guarine, hear him!" exclaimed the Constable, turning hastily to his squire: "He tells me of my disgrace—of the dishonour of my house—of the depravity of those whom I have loved the best in the world—he tells me of it with a calm look, an eye composed, an unfaltering tongue.—Is this—can it be natural? Is De Lacy sunk so low, that his dishonour shall be told by a common strolling minstrel, as calmly as if it were a theme for a vain ballad? Perhaps thou wilt make it one, ha!" as he concluded, darting a furious glance at the minstrel.

"Perhaps I might, my lord," replied the minstrel, "were it not that I must record therein the disgrace of Renault Vidal, who served a lord without either patience to bear insults and wrongs, or spirit to revenge them on the authors of his shame."

"Thou art right, thou art right, good fellow," said the Constable, hastily; "it is vengeance now alone which is left us—And yet upon whom?"

As he spoke he walked shortly and hastily to and fro; and, becoming suddenly silent, stood still and wrung his hands with deep emotion.

Ivanhoe: A Romance

Ivanhoe: A Romance Old Mortality, Complete

Old Mortality, Complete The Pirate

The Pirate Kenilworth

Kenilworth The Black Dwarf

The Black Dwarf A Legend of Montrose

A Legend of Montrose The Monastery

The Monastery The Bride of Lammermoor

The Bride of Lammermoor Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century

Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century St. Ronan's Well

St. Ronan's Well The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day

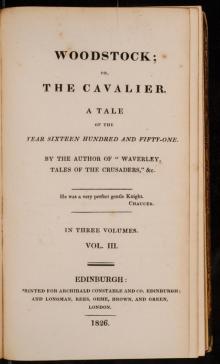

The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day Woodstock; or, the Cavalier

Woodstock; or, the Cavalier_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2) Peveril of the Peak

Peveril of the Peak Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since Old Mortality, Volume 1.

Old Mortality, Volume 1. Waverley Novels — Volume 12

Waverley Novels — Volume 12 The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete Quentin Durward

Quentin Durward Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete

Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete Rob Roy — Complete

Rob Roy — Complete The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2) The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1 Rob Roy — Volume 01

Rob Roy — Volume 01 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01 The Talisman toc-2

The Talisman toc-2 Rob Roy

Rob Roy Old Mortality, Volume 2.

Old Mortality, Volume 2. The Betrothed

The Betrothed Waverley

Waverley The Surgeon's Daughter

The Surgeon's Daughter Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Antiquary

The Antiquary Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft

Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft Trial of Duncan Terig

Trial of Duncan Terig Redgauntlet

Redgauntlet My Aunt Margaret's Mirror

My Aunt Margaret's Mirror Guy Mannering or The Astrologer

Guy Mannering or The Astrologer Marmion

Marmion The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock

The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock Chronicles of the Canongate

Chronicles of the Canongate The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day

The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day The Heart of Mid-Lothian

The Heart of Mid-Lothian Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake