- Home

- Walter Scott

The Talisman toc-2 Page 37

The Talisman toc-2 Read online

Page 37

"Thou art better skilled in brutes than men, De Vaux," said the King.

"I will not deny," said De Vaux, "I have found them ofttimes the honester animals. Also, your Grace is pleased to term me sometimes a brute myself; besides that, I serve the Lion, whom all men acknowledge the king of brutes."

"By Saint George, there thou brokest thy lance fairly on my brow," said the King. "I have ever said thou hast a sort of wit, De Vaux; marry, one must strike thee with a sledge-hammer ere it can be made to sparkle. But to the present gear—is the good knight well armed and equipped?"

"Fully, my liege, and nobly," answered De Vaux. "I know the armour well; it is that which the Venetian commissary offered your highness, just ere you became ill, for five hundred byzants."

"And he hath sold it to the infidel Soldan, I warrant me, for a few ducats more, and present payment. These Venetians would sell the Sepulchre itself!"

"The armour will never be borne in a nobler cause," said De Vaux.

"Thanks to the nobleness of the Saracen," said the King, "not to the avarice of the Venetians."

"I would to God your Grace would be more cautious," said the anxious De Vaux. "Here are we deserted by all our allies, for points of offence given to one or another; we cannot hope to prosper upon the land; and we have only to quarrel with the amphibious republic, to lose the means of retreat by sea!"

"I will take care," said Richard impatiently; "but school me no more. Tell me rather, for it is of interest, hath the knight a confessor?"

"He hath," answered De Vaux; "the hermit of Engaddi, who erst did him that office when preparing for death, attends him on the present occasion, the fame of the duel having brought him hither."

"'Tis well," said Richard; "and now for the knight's request. Say to him, Richard will receive him when the discharge of his devoir beside the Diamond of the Desert shall have atoned for his fault beside the Mount of Saint George; and as thou passest through the camp, let the Queen know I will visit her pavilion—and tell Blondel to meet me there."

De Vaux departed, and in about an hour afterwards, Richard, wrapping his mantle around him, and taking his ghittern in his hand, walked in the direction of the Queen's pavilion. Several Arabs passed him, but always with averted heads and looks fixed upon the earth, though he could observe that all gazed earnestly after him when he was past. This led him justly to conjecture that his person was known to them; but that either the Soldan's commands, or their own Oriental politeness, forbade them to seem to notice a sovereign who desired to remain incognito.

When the King reached the pavilion of his Queen he found it guarded by those unhappy officials whom Eastern jealousy places around the zenana. Blondel was walking before the door, and touched his rote from time to time in a manner which made the Africans show their ivory teeth, and bear burden with their strange gestures and shrill, unnatural voices.

"What art thou after with this herd of black cattle, Blondel?" said the King; "wherefore goest thou not into the tent?"

"Because my trade can neither spare the head nor the fingers," said Blondel, "and these honest blackamoors threatened to cut me joint from joint if I pressed forward."

"Well, enter with me," said the King, "and I will be thy safeguard."

The blacks accordingly lowered pikes and swords to King Richard, and bent their eyes on the ground, as if unworthy to look upon him. In the interior of the pavilion they found Thomas de Vaux in attendance on the Queen. While Berengaria welcomed Blondel, King Richard spoke for some time secretly and apart with his fair kinswoman.

At length, "Are we still foes, my fair Edith?" he said, in a whisper.

"No, my liege," said Edith, in a voice just so low as not to interrupt the music; "none can bear enmity against King Richard when he deigns to show himself, as he really is, generous and noble, as well as valiant and honourable."

So saying, she extended her hand to him. The King kissed it in token of reconciliation, and then proceeded.

"You think, my sweet cousin, that my anger in this matter was feigned; but you are deceived. The punishment I inflicted upon this knight was just; for he had betrayed—no matter for how tempting a bribe, fair cousin—the trust committed to him. But I rejoice, perchance as much as you, that to-morrow gives him a chance to win the field, and throw back the stain which for a time clung to him upon the actual thief and traitor. No!—future times may blame Richard for impetuous folly, but they shall say that in rendering judgment he was just when he should and merciful when he could."

"Laud not thyself, cousin King," said Edith. "They may call thy justice cruelty, thy mercy caprice."

"And do not thou pride thyself," said the King, "as if thy knight, who hath not yet buckled on his armour, were unbelting it in triumph—Conrade of Montserrat is held a good lance. What if the Scot should lose the day?"

"It is impossible!" said Edith firmly. "My own eyes saw yonder Conrade tremble and change colour like a base thief; he is guilty, and the trial by combat is an appeal to the justice of God. I myself, in such a cause, would encounter him without fear."

"By the mass, I think thou wouldst, wench," said the King, "and beat him to boot, for there never breathed a truer Plantagenet than thou."

He paused, and added in a very serious tone, "See that thou continue to remember what is due to thy birth."

"What means that advice, so seriously given at this moment?" said Edith. "Am I of such light nature as to forget my name—my condition?"

"I will speak plainly, Edith," answered the King, "and as to a friend. What will this knight be to you, should he come off victor from yonder lists?"

"To me?" said Edith, blushing deep with shame and displeasure. "What can he be to me more than an honoured knight, worthy of such grace as Queen Berengaria might confer on him, had he selected her for his lady, instead of a more unworthy choice? The meanest knight may devote himself to the service of an empress, but the glory of his choice," she said proudly, "must be his reward."

"Yet he hath served and suffered much for you," said the King.

"I have paid his services with honour and applause, and his sufferings with tears," answered Edith. "Had he desired other reward, he would have done wisely to have bestowed his affections within his own degree."

"You would not, then, wear the bloody night-gear for his sake?" said King Richard.

"No more," answered Edith, "than I would have required him to expose his life by an action in which there was more madness than honour."

"Maidens talk ever thus," said the King; "but when the favoured lover presses his suit, she says, with a sigh, her stars had decreed otherwise."

"Your Grace has now, for the second time, threatened me with the influence of my horoscope," Edith replied, with dignity. "Trust me, my liege, whatever be the power of the stars, your poor kinswoman will never wed either infidel or obscure adventurer. Permit me that I listen to the music of Blondel, for the tone of your royal admonitions is scarce so grateful to the ear."

The conclusion of the evening offered nothing worthy of notice.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

Heard ye the din of battle bray,

Lance to lance, and horse to horse?

GRAY.

It had been agreed, on account of the heat of the climate, that the judicial combat which was the cause of the present assemblage of various nations at the Diamond of the Desert should take place at one hour after sunrise. The wide lists, which had been constructed under the inspection of the Knight of the Leopard, enclosed a space of hard sand, which was one hundred and twenty yards long by forty in width. They extended in length from north to south, so as to give both parties the equal advantage of the rising sun. Saladin's royal seat was erected on the western side of the enclosure, just in the centre, where the combatants were expected to meet in mid encounter. Opposed to this was a gallery with closed casements, so contrived that the ladies, for whose accommodation it was erected, might see the fight without being themselves exposed to view. At either extremity of the

lists was a barrier, which could be opened or shut at pleasure. Thrones had been also erected, but the Archduke, perceiving that his was lower than King Richard's, refused to occupy it; and Coeur de Lion, who would have submitted to much ere any formality should have interfered with the combat, readily agreed that the sponsors, as they were called, should remain on horseback during the fight. At one extremity of the lists were placed the followers of Richard, and opposed to them were those who accompanied the defender Conrade. Around the throne destined for the Soldan were ranged his splendid Georgian Guards, and the rest of the enclosure was occupied by Christian and Mohammedan spectators.

Long before daybreak the lists were surrounded by even a larger number of Saracens than Richard had seen on the preceding evening. When the first ray of the sun's glorious orb arose above the desert, the sonorous call, "To prayer—to prayer!" was poured forth by the Soldan himself, and answered by others, whose rank and zeal entitled them to act as muezzins. It was a striking spectacle to see them all sink to earth, for the purpose of repeating their devotions, with their faces turned to Mecca. But when they arose from the ground, the sun's rays, now strengthening fast, seemed to confirm the Lord of Gilsland's conjecture of the night before. They were flashed back from many a spearhead, for the pointless lances of the preceding day were certainly no longer such. De Vaux pointed it out to his master, who answered with impatience that he had perfect confidence in the good faith of the Soldan; but if De Vaux was afraid of his bulky body, he might retire.

Soon after this the noise of timbrels was heard, at the sound of which the whole Saracen cavaliers threw themselves from their horses, and prostrated themselves, as if for a second morning prayer. This was to give an opportunity to the Queen, with Edith and her attendants, to pass from the pavilion to the gallery intended for them. Fifty guards of Saladin's seraglio escorted them with naked sabres, whose orders were to cut to pieces whomsoever, were he prince or peasant, should venture to gaze on the ladies as they passed, or even presume to raise his head until the cessation of the music should make all men aware that they were lodged in their gallery, not to be gazed on by the curious eye.

This superstitious observance of Oriental reverence to the fair sex called forth from Queen Berengaria some criticisms very unfavourable to Saladin and his country. But their den, as the royal fair called it, being securely closed and guarded by their sable attendants, she was under the necessity of contenting herself with seeing, and laying aside for the present the still more exquisite pleasure of being seen.

Meantime the sponsors of both champions went, as was their duty, to see that they were duly armed and prepared for combat. The Archduke of Austria was in no hurry to perform this part of the ceremony, having had rather an unusually severe debauch upon wine of Shiraz the preceding evening. But the Grand Master of the Temple, more deeply concerned in the event of the combat, was early before the tent of Conrade of Montserrat. To his great surprise, the attendants refused him admittance.

"Do you not know me, ye knaves?" said the Grand Master, in great anger.

"We do, most valiant and reverend," answered Conrade's squire; "but even you may not at present enter—the Marquis is about to confess himself."

"Confess himself!" exclaimed the Templar, in a tone where alarm mingled with surprise and scorn—"and to whom, I pray thee?"

"My master bid me be secret," said the squire; on which the Grand Master pushed past him, and entered the tent almost by force.

The Marquis of Montserrat was kneeling at the feet of the hermit of Engaddi, and in the act of beginning his confession.

"What means this, Marquis?" said the Grand Master; "up, for shame—or, if you must needs confess, am not I here?"

"I have confessed to you too often already," replied Conrade, with a pale cheek and a faltering voice. "For God's sake, Grand Master, begone, and let me unfold my conscience to this holy man."

"In what is he holier than I am?" said the Grand Master.—"Hermit, prophet, madman—say, if thou darest, in what thou excellest me?"

"Bold and bad man," replied the hermit, "know that I am like the latticed window, and the divine light passes through to avail others, though, alas! it helpeth not me. Thou art like the iron stanchions, which neither receive light themselves, nor communicate it to any one."

"Prate not to me, but depart from this tent," said the Grand Master; "the Marquis shall not confess this morning, unless it be to me, for I part not from his side."

"Is this YOUR pleasure?" said the hermit to Conrade; "for think not I will obey that proud man, if you continue to desire my assistance."

"Alas," said Conrade irresolutely, "what would you have me say? Farewell for a while—-we will speak anon."

"O procrastination!" exclaimed the hermit, "thou art a soul-murderer!—Unhappy man, farewell—not for a while, but until we shall both meet no matter where. And for thee," he added, turning to the Grand Master, "TREMBLE!"

"Tremble!" replied the Templar contemptuously, "I cannot if I would."

The hermit heard not his answer, having left the tent.

"Come! to this gear hastily," said the Grand Master, "since thou wilt needs go through the foolery. Hark thee—I think I know most of thy frailties by heart, so we may omit the detail, which may be somewhat a long one, and begin with the absolution. What signifies counting the spots of dirt that we are about to wash from our hands?"

"Knowing what thou art thyself," said Conrade, "it is blasphemous to speak of pardoning another."

"That is not according to the canon, Lord Marquis," said the Templar; "thou art more scrupulous than orthodox. The absolution of the wicked priest is as effectual as if he were himself a saint—otherwise, God help the poor penitent! What wounded man inquires whether the surgeon that tends his gashes has clean hands or no? Come, shall we to this toy?"

"No," said Conrade, "I will rather die unconfessed than mock the sacrament."

"Come, noble Marquis," said the Templar, "rouse up your courage, and speak not thus. In an hour's time thou shalt stand victorious in the lists, or confess thee in thy helmet, like a valiant knight."

"Alas, Grand Master," answered Conrade, "all augurs ill for this affair, the strange discovery by the instinct of a dog—the revival of this Scottish knight, who comes into the lists like a spectre—all betokens evil."

"Pshaw," said the Templar, "I have seen thee bend thy lance boldly against him in sport, and with equal chance of success. Think thou art but in a tournament, and who bears him better in the tilt-yard than thou?—Come, squires and armourers, your master must be accoutred for the field."

The attendants entered accordingly, and began to arm the Marquis.

"What morning is without?" said Conrade.

"The sun rises dimly," answered a squire.

"Thou seest, Grand Master," said Conrade, "nought smiles on us."

"Thou wilt fight the more coolly, my son," answered the Templar; "thank Heaven, that hath tempered the sun of Palestine to suit thine occasion."

Thus jested the Grand Master. But his jests had lost their influence on the harassed mind of the Marquis, and notwithstanding his attempts to seem gay, his gloom communicated itself to the Templar.

"This craven," he thought, "will lose the day in pure faintness and cowardice of heart, which he calls tender conscience. I, whom visions and auguries shake not—-who am firm in my purpose as the living rock—I should have fought the combat myself. Would to God the Scot may strike him dead on the spot; it were next best to his winning the victory. But come what will, he must have no other confessor than myself—our sins are too much in common, and he might confess my share with his own."

While these thoughts passed through his mind, he continued to assist the Marquis in arming, but it was in silence.

The hour at length arrived; the trumpets sounded; the knights rode into the lists armed at all points, and mounted like men who were to do battle for a kingdom's honour. They wore their visors up, and riding around the lists three times, showed t

hemselves to the spectators. Both were goodly persons, and both had noble countenances. But there was an air of manly confidence on the brow of the Scot—a radiancy of hope, which amounted even to cheerfulness; while, although pride and effort had recalled much of Conrade's natural courage, there lowered still on his brow a cloud of ominous despondence. Even his steed seemed to tread less lightly and blithely to the trumpet-sound than the noble Arab which was bestrode by Sir Kenneth; and the SPRUCH-SPRECHER shook his head while he observed that, while the challenger rode around the lists in the course of the sun—that is, from right to left—the defender made the same circuit WIDDERSINS—that is, from left to right—which is in most countries held ominous.

A temporary altar was erected just beneath the gallery occupied by the Queen, and beside it stood the hermit in the dress of his order as a Carmelite friar. Other churchmen were also present. To this altar the challenger and defender were successively brought forward, conducted by their respective sponsors. Dismounting before it, each knight avouched the justice of his cause by a solemn oath on the Evangelists, and prayed that his success might be according to the truth or falsehood of what he then swore. They also made oath that they came to do battle in knightly guise, and with the usual weapons, disclaiming the use of spells, charms, or magical devices to incline victory to their side. The challenger pronounced his vow with a firm and manly voice, and a bold and cheerful countenance. When the ceremony was finished, the Scottish Knight looked at the gallery, and bent his head to the earth, as if in honour of those invisible beauties which were enclosed within; then, loaded with armour as he was, sprung to the saddle without the use of the stirrup, and made his courser carry him in a succession of caracoles to his station at the eastern extremity of the lists. Conrade also presented himself before the altar with boldness enough; but his voice as he took the oath sounded hollow, as if drowned in his helmet. The lips with which he appealed to Heaven to adjudge victory to the just quarrel grew white as they uttered the impious mockery. As he turned to remount his horse, the Grand Master approached him closer, as if to rectify something about the sitting of his gorget, and whispered, "Coward and fool! recall thy senses, and do me this battle bravely, else, by Heaven, shouldst thou escape him, thou escapest not ME!"

Ivanhoe: A Romance

Ivanhoe: A Romance Old Mortality, Complete

Old Mortality, Complete The Pirate

The Pirate Kenilworth

Kenilworth The Black Dwarf

The Black Dwarf A Legend of Montrose

A Legend of Montrose The Monastery

The Monastery The Bride of Lammermoor

The Bride of Lammermoor Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century

Redgauntlet: A Tale Of The Eighteenth Century St. Ronan's Well

St. Ronan's Well The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day

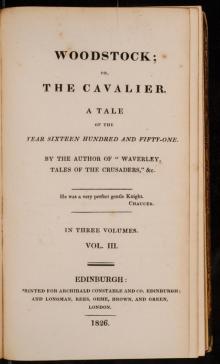

The Fair Maid of Perth; Or, St. Valentine's Day Woodstock; or, the Cavalier

Woodstock; or, the Cavalier_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 1 (of 2) Peveril of the Peak

Peveril of the Peak Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since Old Mortality, Volume 1.

Old Mortality, Volume 1. Waverley Novels — Volume 12

Waverley Novels — Volume 12 The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Complete Quentin Durward

Quentin Durward Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete

Waverley; Or 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Complete Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer — Complete Rob Roy — Complete

Rob Roy — Complete The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 2 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Complete_preview.jpg) Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2)

Anne of Geierstein; Or, The Maiden of the Mist. Volume 2 (of 2) The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1

The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Volume 1 Rob Roy — Volume 01

Rob Roy — Volume 01 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 2 Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1

Waverley; Or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since — Volume 1 Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01

Guy Mannering, Or, the Astrologer — Volume 01 The Talisman toc-2

The Talisman toc-2 Rob Roy

Rob Roy Old Mortality, Volume 2.

Old Mortality, Volume 2. The Betrothed

The Betrothed Waverley

Waverley The Surgeon's Daughter

The Surgeon's Daughter Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Ivanhoe (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Antiquary

The Antiquary Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft

Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft Trial of Duncan Terig

Trial of Duncan Terig Redgauntlet

Redgauntlet My Aunt Margaret's Mirror

My Aunt Margaret's Mirror Guy Mannering or The Astrologer

Guy Mannering or The Astrologer Marmion

Marmion The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock

The Tapestried Chamber, and Death of the Laird's Jock Chronicles of the Canongate

Chronicles of the Canongate The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day

The Fair Maid of Perth or St. Valentine's Day The Heart of Mid-Lothian

The Heart of Mid-Lothian Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake